"She hated him, she hated herself, she hated her beauty that had brought this horror upon her."

-- from The Sheik (82)

Spoiler warning, and a trigger warning, too. Sorry, but you're going to want to know what you're getting into.

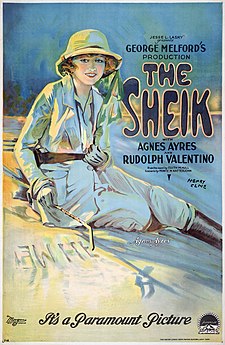

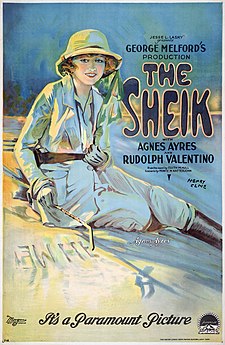

This 1919 work has an important place in the history of the romance novel, selling over a million copies before spinning off the fabulously famous Rudolph Valentino film and the much-recorded song "The Sheik of Araby." I understand full-well that this is a period piece, and I grew up in the time of The Flame and the Flower and Luke and Laura, so I know this kind of narrative clearly appeals to some people, a fantasy that circumvents then-contemporary restrictions on women's sexual autonymy. But I was still surprised how much this influential book is a love letter to Stockholm Syndrome.

British beauty Diana Mayo, brought up by her brother as if she were a boy, is indifferent to romance and basically asexual. With a government-approved guide, but no proper male chaperone, she embarks on a month-long trip through the Algerian desert, laughing off any dangers related to her gender. The trip is a long-time dream, beautifully described: "It was the desert at last, the desert that she felt she had been longing for all her life. She had never known until this moment how intense the longing had been. She felt strangely at home, as if the great, silent emptiness had been waiting for her as she had been waiting for it, and now that she had come it was welcoming her softly with the faint rustle of the whispering sand ..." (24)

On the cusp of feeling true freedom for the first time in her life, Diana's group is attacked by Arab tribesmen led by the handsome Ahned Ben Hassain, and then, there's no sugar-coating it. He kidnaps and rapes her. "She had paid heavily for the determination to ignore the restrictions of her sex laid upon her and the payment was not yet over" (88). None of this is a crime of passion or opportunity: it's a planned, premeditated kidnapping and rape, a conspiracy in which her guide was bribed and the bullets in her gun previously replaced with blanks.

Hull does a masterful job in describing Diana's pain, humiliation, and despair as she's kept in a situation of long-term abuse by a man who says he'll stop raping her "when I am tired of you," and "better me than my men" (81, 90). Her skill here makes it all the more disturbing when, following a thwarted escape attempt, Diana is suddenly struck by the inevitable realization that she's fallen in love with her abuser, and the story starts to work on his eventual repentance and redemption.

You should also be aware there are various casual racial slurs, and a lot of assumption of British superiority over the Arabs, although "Western civilization" doesn't come off all that well either.

This is a well-written book, it's an interesting historical document, but as much as I tried, it's hard not to see it as pretty unsavory through modern eyes.

Hull, E.M. The Sheik. Philadelphia: Pine Street Books, 2001.

Hull, E.M. The Sheik. Philadelphia: Pine Street Books, 2001.

-- from The Sheik (82)

Spoiler warning, and a trigger warning, too. Sorry, but you're going to want to know what you're getting into.

This 1919 work has an important place in the history of the romance novel, selling over a million copies before spinning off the fabulously famous Rudolph Valentino film and the much-recorded song "The Sheik of Araby." I understand full-well that this is a period piece, and I grew up in the time of The Flame and the Flower and Luke and Laura, so I know this kind of narrative clearly appeals to some people, a fantasy that circumvents then-contemporary restrictions on women's sexual autonymy. But I was still surprised how much this influential book is a love letter to Stockholm Syndrome.

British beauty Diana Mayo, brought up by her brother as if she were a boy, is indifferent to romance and basically asexual. With a government-approved guide, but no proper male chaperone, she embarks on a month-long trip through the Algerian desert, laughing off any dangers related to her gender. The trip is a long-time dream, beautifully described: "It was the desert at last, the desert that she felt she had been longing for all her life. She had never known until this moment how intense the longing had been. She felt strangely at home, as if the great, silent emptiness had been waiting for her as she had been waiting for it, and now that she had come it was welcoming her softly with the faint rustle of the whispering sand ..." (24)

On the cusp of feeling true freedom for the first time in her life, Diana's group is attacked by Arab tribesmen led by the handsome Ahned Ben Hassain, and then, there's no sugar-coating it. He kidnaps and rapes her. "She had paid heavily for the determination to ignore the restrictions of her sex laid upon her and the payment was not yet over" (88). None of this is a crime of passion or opportunity: it's a planned, premeditated kidnapping and rape, a conspiracy in which her guide was bribed and the bullets in her gun previously replaced with blanks.

Hull does a masterful job in describing Diana's pain, humiliation, and despair as she's kept in a situation of long-term abuse by a man who says he'll stop raping her "when I am tired of you," and "better me than my men" (81, 90). Her skill here makes it all the more disturbing when, following a thwarted escape attempt, Diana is suddenly struck by the inevitable realization that she's fallen in love with her abuser, and the story starts to work on his eventual repentance and redemption.

You should also be aware there are various casual racial slurs, and a lot of assumption of British superiority over the Arabs, although "Western civilization" doesn't come off all that well either.

This is a well-written book, it's an interesting historical document, but as much as I tried, it's hard not to see it as pretty unsavory through modern eyes.

The edition I read was from a University of Pennsylvania imprint, in a high-quality facsimile style. I did wish it had some background information about the novel and about Hull, who apparently did travel in Algeria before marrying and settling on an estate. This is a novel that cries out for contextualization! I haven't watched the movie yet, but a synopsis tells me that while the desert sequences play out much the same way, the Valentino version of the Sheik "considers forcing himself upon her, but decides against it" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sheik_(film)).