This year saw a Volume Two of The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories come out from the amazing people at Valancourt Books. Because I'm not made of stone, I didn't even try to save it for Christmas itself, but I did read it in December, when there was snow on the ground. I loved everything in it, and ordered another novel by Grant Allen because of the story in here. If I had the funds, I'd buy tons of both volumes, and send the pair to everyone I know. And you'd like it!

Other highlights of contemporary reading from 2017, including two things published this year, which, in my life, is practically unheard of.

My Best Friend's Exorcism (2016), by Grady Hendrix. Scary, funny, gross, and heart-warming, all at once. I rushed out to read his previous Horrorstor (2014), and also the 2017 non-fiction Paperbacks from Hell, which are both also HIGHLY recommended.

The Essex Serpent (2017), by Sarah Perry. From the blurbs, I didn't even know what genre I was in, and all throughout reading, I had no idea where it was going. It's not horror, but it's certainly full of uncanny atmosphere. I loved it, and look forward to whatever she does next.

Zombies from the Pulps! (2014), edited by Jeffrey Shanks (Skelos Press). Full disclosure: I know the editor, and have been published in the Skelos journal. However, if I hadn't really liked this collection of classic pulp stories about all kinds of zombies (voodoo, mad scientists, sometimes both!), I just wouldn't have mentioned it. As it was, I was a little late getting around to it, but this was a super-fun read, one of my favorites of the year.

Ride the Star Wind: Cthulhu, Space Opera, and the Cosmic Weird (2017), edited by Scott Gable & C. Dombrowski. The subtitle sounds like a non-fiction work of literary criticism, but it's not. I discovered this when I met the people from Broken Eye Books at the Providence NecronomiCon. Normally (despite some of my above recommendation), I'm not a real fan of short stories, but I was very impressed by this collection of deep-space, far-future sci-fi takes on themes from the Lovecraft mythos. Their earlier collection, Tomorrow's Cthulhu, is on my list for future reading.

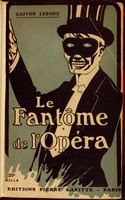

All the above, by the way, have very different, but really great cover art. We seem to be in a golden age for that!

Other highlights of contemporary reading from 2017, including two things published this year, which, in my life, is practically unheard of.

My Best Friend's Exorcism (2016), by Grady Hendrix. Scary, funny, gross, and heart-warming, all at once. I rushed out to read his previous Horrorstor (2014), and also the 2017 non-fiction Paperbacks from Hell, which are both also HIGHLY recommended.

The Essex Serpent (2017), by Sarah Perry. From the blurbs, I didn't even know what genre I was in, and all throughout reading, I had no idea where it was going. It's not horror, but it's certainly full of uncanny atmosphere. I loved it, and look forward to whatever she does next.

Zombies from the Pulps! (2014), edited by Jeffrey Shanks (Skelos Press). Full disclosure: I know the editor, and have been published in the Skelos journal. However, if I hadn't really liked this collection of classic pulp stories about all kinds of zombies (voodoo, mad scientists, sometimes both!), I just wouldn't have mentioned it. As it was, I was a little late getting around to it, but this was a super-fun read, one of my favorites of the year.

Ride the Star Wind: Cthulhu, Space Opera, and the Cosmic Weird (2017), edited by Scott Gable & C. Dombrowski. The subtitle sounds like a non-fiction work of literary criticism, but it's not. I discovered this when I met the people from Broken Eye Books at the Providence NecronomiCon. Normally (despite some of my above recommendation), I'm not a real fan of short stories, but I was very impressed by this collection of deep-space, far-future sci-fi takes on themes from the Lovecraft mythos. Their earlier collection, Tomorrow's Cthulhu, is on my list for future reading.

All the above, by the way, have very different, but really great cover art. We seem to be in a golden age for that!

And a huge thanks to Tartarus Press for providing me with beautiful new (limited) editions of Arthur Machen's fantastic memoirs. Far Off Things and Things Near and Far are collected in The Autobiography of Arthur Machen, and The London Adventure volume contains many of Machen's additional essays on London life. Plus an also lovely but very affordable paperback edition of his long out-of-print collaboration with A.E. Waite, The House of the Hidden Light, which I recently reviewed here.

Looking forward to the books that the new year will bring.