"The world has no pity on a man who can't do or produce something it thinks worth money. You may be a divine poet, and if some good fellow doesn't take pity on you you will starve by the roadside. Society is as blind and brutal as fate." -- Struggling novelist Edwin Reardon tries to explain the reality of the situation to his wife in New Grub Street (p. 230)

I started off merrily underlining satirical comments by the ambitious young writer Jasper Milvain, thinking how much I was already enjoying this book. Before I knew it, it turned into one of the most depressing novels I've read in a long time. Not Hans Christian Andersen depressing, but still.

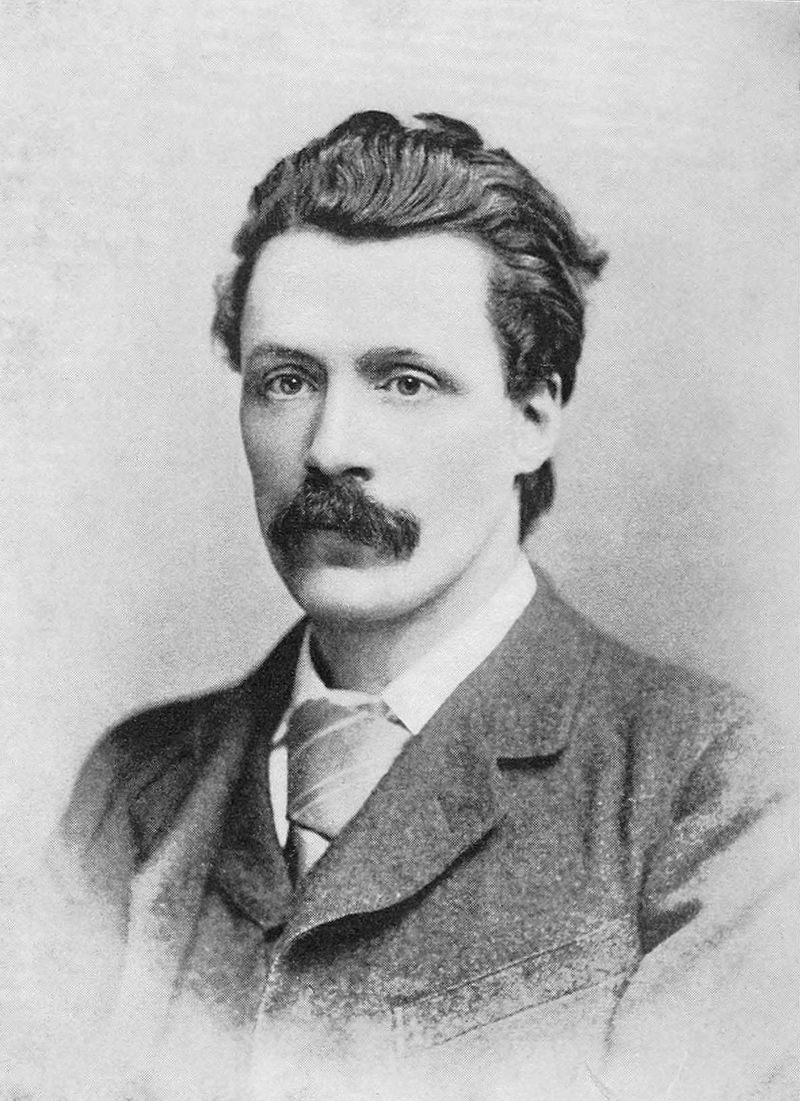

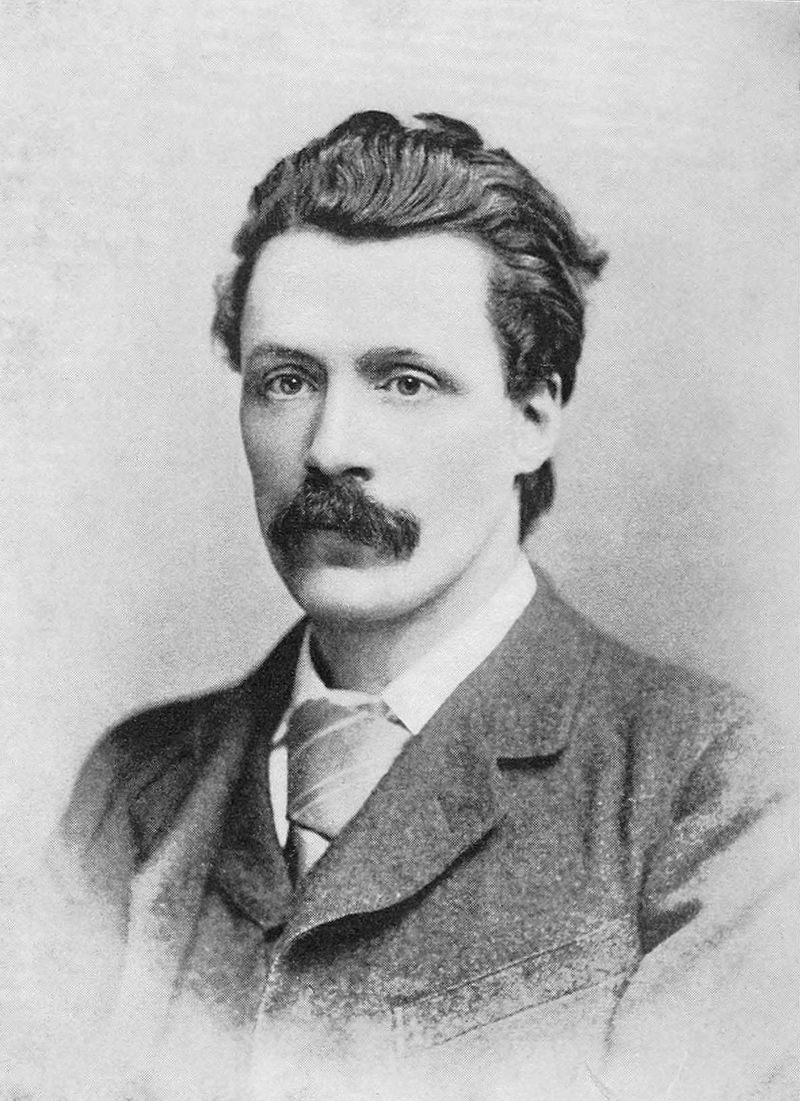

Published in 1891 but set a decade earlier, the novel follows a cross-section of characters who are "dwellers in the valley of the shadow of books" (48). The realistic Milvain is willing to follow whatever trend presents itself, saying "let us use our wits to earn money, and make the best we can of our lives" (43), in contrast with the romantic Edwin Reardon, a sensitive scholar who strives to produce work of value, but whose young wife, originally proud of her literary husband, is completely unprepared for the struggle that ensues. Writers, editors, men and women, young and elderly, all those involved are ground down by "the business of literature" (53).

There's a whole subplot about the incompatibility of Reardon and his wife, Amy. Gissing seems pretty unsympathetic to her situation, especially once they have a child to support, but it's somewhat redeemed by the critique of attitudes about divorce. After what's supposed to be a temporary separation, Reardon writes: "You have no love for me, and where there is no love there is no mutual obligation in marriage ... Have more courage; refuse to act falsehoods; tell society it is base and brutal, and that you prefer to live an honest life" (418).

Early on, when he was still hopeful of success as a novelist despite his noncommercial style, Amy advised him to"do a certain number of pages every day. Good or bad, never mind; let the pages be finished" (86). Just like Nanowrimo! (Except he has to get his straight-away to his publisher, so there's a bit more pressure).

Probably my favorite character was the ineffectual Mr. Biffen, who toils throughout the novel on a hyper-realistic novel called Mr. Bailey, Grocer, which he knows full well will have zero success. If it existed, I'd put it on my Classics Club list right now!

Gissing, George R. New Grub Street.. Ed, Intr. by Bernard Bergonzi. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1985.

I started off merrily underlining satirical comments by the ambitious young writer Jasper Milvain, thinking how much I was already enjoying this book. Before I knew it, it turned into one of the most depressing novels I've read in a long time. Not Hans Christian Andersen depressing, but still.

Published in 1891 but set a decade earlier, the novel follows a cross-section of characters who are "dwellers in the valley of the shadow of books" (48). The realistic Milvain is willing to follow whatever trend presents itself, saying "let us use our wits to earn money, and make the best we can of our lives" (43), in contrast with the romantic Edwin Reardon, a sensitive scholar who strives to produce work of value, but whose young wife, originally proud of her literary husband, is completely unprepared for the struggle that ensues. Writers, editors, men and women, young and elderly, all those involved are ground down by "the business of literature" (53).

There's a whole subplot about the incompatibility of Reardon and his wife, Amy. Gissing seems pretty unsympathetic to her situation, especially once they have a child to support, but it's somewhat redeemed by the critique of attitudes about divorce. After what's supposed to be a temporary separation, Reardon writes: "You have no love for me, and where there is no love there is no mutual obligation in marriage ... Have more courage; refuse to act falsehoods; tell society it is base and brutal, and that you prefer to live an honest life" (418).

Early on, when he was still hopeful of success as a novelist despite his noncommercial style, Amy advised him to"do a certain number of pages every day. Good or bad, never mind; let the pages be finished" (86). Just like Nanowrimo! (Except he has to get his straight-away to his publisher, so there's a bit more pressure).

Probably my favorite character was the ineffectual Mr. Biffen, who toils throughout the novel on a hyper-realistic novel called Mr. Bailey, Grocer, which he knows full well will have zero success. If it existed, I'd put it on my Classics Club list right now!

Gissing, George R. New Grub Street.. Ed, Intr. by Bernard Bergonzi. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1985.

No comments:

Post a Comment